CHINA

China, or more correctly, the People’s Republic of China, has had one of the longest single unified civilizations in the world. There have been settlements on the land now known as eastern China since around 8,000-5,000 BC. Consequently, their history is as vast as their land, and even a superficial review of that history would be well beyond the scope of this webpage. Rather than try to review China’s vast history, this page will only lightly touch on historical eras or events that are relevant to understanding subsequent eras or events or our experiences while in China.

Imperial China was ruled by subsequent dynasties from approximately 1600 BC to 1911 AD. Although changes in dynastic rule have not always been synonymous with significant turning points in China’s history, changes of dynasties provide convenient time references from which China’s vast history can be viewed. A few of these dynasties warrant mention.

China’s first dynasty, the Shang dynasty (~1600-1000BC) developed the precursor of China’s ideographic writing system. This enabled their civilization to advance to a level of sophistication comparable to those in Europe and the Middle East at that time.

The basis of Chinese philosophical thought was developed during the Zhou dynasties (1066-221 BC). This development was led by Lao-tse, Confucius, Mo Ti, and Mencius.

China’s feudal states, which were often at war with one another, were first united during the Qin dynasty under Emporer Qin Shi Huang (ruled 221-210 BC). (In China, the letter “Q” is pronounced “ch”, thus, “Qin” is pronounced “chin” – the origin of the name China.) Emporer Qin Shi Huang also began work on the Great Wall to deter invasion from the north and west.

The Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) is often considered the ‘golden age’ of China. Painting, sculpture, and poetry flourished during this era, and books were mass produced.

China was invaded by northern Mongols and captured by Gengis Khan in 1215. Khan’s grandson, Kublai Khan, established the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 AD) which was subsequently overthrown by the Mings.

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD) was a long and stable period in China. The Mings moved the capital to Beijing and created a traditional city with the Forbidden City at its center, four altars at the cardinal points, and a wall around all for protection and enclosure. The Mings reinforced and completed the Great Wall. They also developed China’s maritime industry and produced large amounts of porcelain and silk.

However, other northern invaders – this time the Manchus – overthrew the Ming Dynasty in 1644 and established the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 AD). China remained mostly isolated during most of these years, but by the end of the 18th century, Canton and Macao were open to foreign traders. However, by the end of the 19th century, they had been forced to open further ports to trade and to cede Hong Kong to Britain. China’s final emperor, a child named Pu-Yi, was overthrown by Sun Yat Sen in 1911.

Sun Yat Sen inaugurated the Provisional Chinese Republic on January 1, 1912, and became its first president. He resigned in favor of Yuan Shikai who sought to become emperor; however, Yuan was also forced to resign. Civil war erupted, and General Chiang Kai Shek (1887–1975), a communist, soon occupied most of China and set up the Kuomintang (KMT) regime in 1928. He broke from the communists shortly thereafter.

Japan invaded China in 1931, and most of China united behind Chiang. As Japan seized most of the eastern seaports and railways, the KMT retreated to Chongqing. When Japan surrendered to the Western Allies in 1945, civil war erupted again – this time between the KMT forces and the communist forces behind Mao Zedong. The KMT were overwhelmed by the Soviet-supported communists, and Chiang fled to Taiwan.

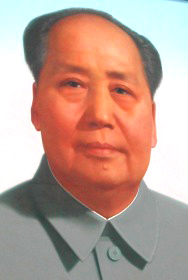

Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Beijing was designated as its capital, and Zhou Enlai was named as premier.

Historians have described Mao’s actions and their consequences, and much of it is difficult to comprehend. Rather than trying to promote any understanding of the incomprehensible, the following only mentions some of the actions for which Mao is most remembered.

In mid-1950, less than one year after seizing power, Mao led the communist bloc in supporting North Korea in the Korean War. In November of 1950, he sent troops to assist the North Koreans.

Also in 1950, Mao invaded and annexed Tibet. Over the next two decades, more than a million Tibetans died either at the hands of the Chinese or from famine resulting from incompetent agricultural policies. Tibet’s cultural heritage was razed, and over 6,000 monasteries were destroyed.

In 1958, Mao instituted the “Great Leap Forward” campaign which was supposed to restructure China’s primarily agrarian economy through a combination of rural communes and village industrialization. The result was widespread famine that killed more than 20 million Chinese people.

However, Mao’s greatest claim to infamy is the Cultural Revolution which started in early 1966, and ended only after his death in 1976. The Cultural Revolution was to rid China of “old ideas, old culture, old habits, and old customs” – essentially destroy their history. Schools were closed. Irreplaceable cultural relics were destroyed. Millions were killed in violent purges. Mao died on September 10, 1976.

After Mao’s death, repressed intraparty rivalries erupted. Mao’s widow and three of her associates – known as the Gang of Four – were arrested, tried, and convicted for activities undermining the party, government, and economy. Zhou Enlai had died and was succeeded by Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. Deng was removed from office but reinstated within a year. However, despite the turmoil, Beijing and Washington established full diplomatic relations on January 1, 1979 – around the same time that China sent troops to Vietnam’s northern border in support of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge.

Deng introduced some massive changes in China. Their communist ideology was substantially reinterpreted, and they instituted nationwide economic changes. The military commission cited the Cultural Revolution as a “grave blunder” and sought to diminish the widespread idolatry of Mao. Marxist tenets were replaced with Western technology and management techniques. Deng introduced economic freedoms but not political freedom.

In 1989, pro-democracy demonstrators gathered in Beijing’s Tianamen Square and called for political reforms. The demonstrations, as well as many of the demonstrators, were crushed by military troops and tanks. Hundreds were killed.

In the intervening years, China has moved ahead with great speed in some areas, and it has clung to its past in other areas. Hong Kong and Macau have both returned to Chinese sovereignty. China was admitted to the World Trade Organization. China has put a man into space. However, the gap between the rich and poor continues to widen, and China’s human rights abuses are myriad. Although China now has the 3rd largest economy in the world, they still lag behind much of the world in social issues.

China is very large – as large as the United States. It is comprised of 3.7 million square miles of land. It spans more than 50 degrees of latitude, has a Pacific coastline 12,400 miles long, and is bordered by 14 countries.

Its vast lands can be categorized in three steps of decreasing altitude from west to east: 1) the Tibetan plateau, 2) the central mountains, and 3) the fertile lowlands. The westernmost Tibetan plateau is mostly over 13,000 feet elevation, the central mountains range from 5,000 to 10,000 feet elevation, and the fertile lowlands range from 5,000 feet to the coast. . China contains the world’s highest peak – Mt. Everest – at 29,029 feet and the second lowest area – Turpan Depression – at 505 feet below sea level. Sixty five percent of the land is high ground and sparsely populated.

China’s rivers run from the western highlands toward the eastern sea coast. Consequently, the eastern coastal areas are densely populated and intensely farmed. China’s best known river, the Yangtze, is the third longest river in the world at 2,500 miles.

China’s population is approximately 1.3 billion, and approximately 75% live in rural areas. China’s population comprises nearly 20% of the world’s population. Although there are 55 recognized minority groups in China, they comprise only 7% of the total population. Ninety three percent of China’s populations are “Han” – the majority ethnic group. Approximately 50% of China’s population works in agriculture (down from 70% just a few years ago), 22% work in industry, and 28% work in services.

China’s national language is Mandarin; however, there are many regional dialects. Their written script, which has been traced back to around 1300 BC, is used consistently throughout the country. Therefore, some Chinese may not understand the spoken language of some of their countrymen, but they will share a written language.

China’s monetary unit is the yuan. At present, the yuan is approximately equivalent to thirteen cents in U.S currency.

Family life in China is experiencing many changes. Most Chinese our ages are in arranged marriages. These marriages were arranged by their families, and they were approved by their work units. Today, however, most Chinese select their own spouses, and divorce has become common. However, the one-child policy remains. There are numerous convoluted rules which outline the circumstances under which a woman may bear a second child, but we understood only a few of them. If a woman’s first-born child is male, she may not have any more children. However, if her first-born is female, she may try again to have a male. If she has two females, she may not have a third child. Any subsequent pregnancies must be aborted.

China appears to be at a crossroad. They seem to want to maintain traditions on one hand that are inconsistent with changes adopted on the other hand – or so it appears to the casual visitor. China’s past is very interesting. So will be its future.

On our third day we again had heavy fog in the morning. We were approaching Gibralter and maneuvering our way through a lot of anchored and anchoring ships. Thank goodness for our radar!

The marinas in Gibralter are known for being unfriendly to cruising boats, and they almost always send them away. We went to Alcaidesa Marina less than 100 yards from the border with Gibralter. Alcaidesa Marina is in the town of La Linea, Spain.

This trip was different from any other that we have taken in that we went with a ‘tour’. We chose to do this for a few reasons, but language was our primary reason. We can fake a little Spanish or French, but not a language written in different characters, and we could not learn enough quickly enough to even get by. Having a bilingual ‘guide’ seemed a necessity.

The ‘tour’ also facilitated us doing as much travel within China as we did (we took four domestic flights, two boat trips, and traveled a few hundred miles by road). We did not have to arrange flights, hotels, cars, boats, cabs, meals, etc. These would have been difficult tasks without language skills.

Finally, it was a good value for the dollar. We could not have done all we did for what we spent on an ‘all inclusive’ tour.

The disadvantages? Our schedules were not flexible unless our entire group decided to make a change. We did this only a few times. We were somewhat wed to a predetermined schedule, but fortunately we were happy with the itinerary/schedule we had selected.

Would we do a ‘tour’ again? Yes, in some situations. We would certainly go with a tour again in a country where we have no language skills whatsoever. We would also go with a tour group in a country in which we did not feel comfortable branching out on our own. It has limitations, but the advantages outweighed the disadvantages for us on this trip.

Even if we were not traveling with a group, we would have probably needed to join a tour of some sort within China. Most hotels arrange for guests to join tours to the popular sites.

Tour guides in China are government-trained and licensed, and they speak government speak. They toe the party line. Travel in China definitely has a political undertone.

The number of tourists in China is astounding. We asked our guide how many people visit the Forbidden City each day, and she said that one million people per day pass through there during the busy season. One million per day! And that is only one site in one city. The numbers, and the associated income for the Chinese government, is tremendous. And China continues to increase in popularity as a travel destination. The World Tourism Organization predicts by 2020, China will be the world’s most popular tourist destination.

China’s current organization has created 31 provinces and two autonomous municipalities – Beijing and Shanghai. Our itinerary included four provinces and both Beijing and Shanghai. We wanted to see the popular sites. We couldn’t imagine traveling to China without seeing the Forbidden City or the Great Wall. We also wanted to see those sites that sounded particularly interesting to us. We ‘had to’ see the Terracotta Army. And we wanted to see things slightly off the beaten path. That is why we traveled to southwest China. All in all, we were pleased with our choices.

We traveled from Bundaberg, Australia. We took a short flight from Bundaberg to Brisbane, Australia. From there we flew with Singapore Airlines (highly recommended) through Singapore to Beijing. Our return was from Shanghai and also through Singapore and Brisbane to Bundaberg. Our itinerary within China follows.

Northern China – We started our visit in the north. We flew in to Beijing which offers a wealth of history from the 15th century forward. Then we flew to Xian (Shaanxi province). Xian’s history is most colorful from the 3rd century BC through the early 15th century AD. We then flew from Xian to Wuhan.

Central China – We moved in to and through central China along the Yangtse River. We arrived in Wuhan (Hubei province), and then we drove a few hundred miles west. We boarded a boat to continue exploring westward up the Yangtse River.

Southwestern China – We began exploring southwestern China when we disembarked from our Yangtse River trip in Chongqing (Chongqing province). We flew from Chongqing to Guilin (Guangxi province), and then we took a day trip on the Li River to Yangshuo (also Guangxi province). We drove back to Guilin, and then we flew to Shanghai. Shanghai, an autonomous municipality on the eastern coast of the central region of China, was our last stop in China.

The good – The good aspects of this trip came from both what we saw and what we learned. We have written thumbnail sketches of many things we saw and provided links and a few pictures. Seeing sites such as the Forbidden City enables one to imagine the grandeur of the time when it was the functional capital of China. We also learned a lot more about China’s history as we visited historic sites. We both also believe that we learned a lot that was not on the itinerary. China has only recently emerged from its lengthy self-imposed isolation, and it is interesting to observe its ‘opening’ process. The Chinese government may be an emerging world power in some ways; however, the Chinese people are still essentially a peasant population. Many contrasts.

The bad – Although we experienced a few small annoyances, we had substantial problems with one particular issue traveling China – artificiality. There is a difference between a ‘restoration’ and a ‘recreation’. Most of what we saw was recreation. Many of China’s historic sites have either deteriorated with age or were intentionally destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. They have been rebuilt to look like the original, but they have little else in common with the original.

For instance, the Great Wall is crumbling badly. However, there are a few places where it has been ‘restored’, and those are the only places tourists are taken to see and ‘experience’ the wall. The wall has not been ‘restored’ to its previous condition; it has been recreated including concrete steps and iron pipe handrails. After climbing for an hour or two, you reach a summit to find that the arrow tower is now a souvenir shop. It has become something like a Disneyland ride.

This is the case throughout the areas of China we visited. We visited a relatively remote temple on the banks of the Yangtze River, and only after asking we learned that the entire temple, including all statues, was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Everything we saw at this temple was recreated during the past 30 years. Far too much of what we saw was a recreation.

When we go to Rome, we want to see the ruins of the ‘real’ Coliseum, not a late-20th century recreation. We expected the same in China, but that is not what we found.

The ugly – We found the pollution in China intolerable. We thought the air pollution was particularly intolerable because we could see it. If we could have seen the pesticides and chemicals in our food, we might feel similarly about that. Although Beijing was the worst pollution we saw, it was not restricted to Beijing or the bigger cities – it was everywhere. As we note on our ‘Shanghai’ page, we could not see buildings across the river or a block away. We could not even see the tops of buildings which we stood next to. It really is quite horrible.

Having said all this, we are still glad we went. And we hope you will follow us to China and see some of the interesting sites we saw.

Follow us to our first stop in China, Beijing, or return to our land travel page.